Selected coverage: NY Times, Christian Science Monitor, The Telegraph, The Independent, Daily Mail

Good directions start — literally — with the most obvious

To give good directions, it is not enough to say the right things: saying them in the right order is also important, shows a study in Frontiers in Psychology. Sentences that start with a prominent landmark and end with the object of interest work better than sentences where this order is reversed. These results could have direct applications in the fields of artificial intelligence and human-computer interaction.

“Here we show for the first time that people are quicker to find a hard-to-see person in an image when the directions mention a prominent landmark first, as in ‘Next to the horse is the man in red’, rather than last, as in ‘The man in red is next to the horse’,” says Alasdair Clarke from the School of Psychology at the University of Aberdeen, the lead author of the study.

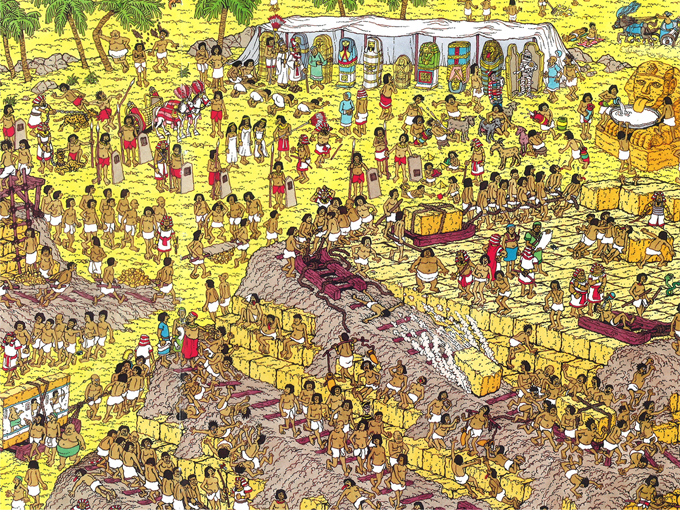

Clarke et al. asked volunteers to focus on a particular human figure within the visually cluttered cartoons of the ‘Where’s Wally?’ children’s books (called ‘Where’s Waldo?’ in the USA and Canada). The volunteers were then instructed to explain, in their own words, how to find that figure quickly — no trivial task, as each cartoon contained hundreds of items. As expected, the volunteers often opted to indicate the position of the human figure relative to a landmark object in the cartoon, such as a building.

What was surprising, however, was that they tended to use a different word order depending on the visual properties of the landmark. Landmarks that stood out strongly from the background — as measured with imaging software — were statistically likely to be mentioned at the beginning of the sentence, while landmarks that stood out little were typically mentioned at its end. But if the target figure itself stood out strongly, most participants mentioned that first.

In a separate experiment, the researchers show that the most frequently used word order, ‘landmark first-target-second’, is also the most effective: people who heard descriptions with this order needed on average less time to find the human figure in the cartoon than people who heard descriptions with the reverse order.

These results suggest that people who give directions keep a mental record of which objects in an image are easy to see, prefer to use these as landmarks, and treat them differently than harder-to-see objects when planning the word order of descriptions. This strategy helps listeners to find the target quickly.

“Listeners start processing the directions before they’re finished, so it’s good to give them a head start by pointing them towards something they can find quickly, such as a landmark. But if the target your listener is looking for is itself easy to see, then you should just start your directions with that,” concludes co-author Micha Elsner, Assistant Professor at the Department of Linguistics, Ohio State University.

These results could help to develop computer algorithms for automatic direction-giving. “A long-term goal is to build a computer direction-giver that could automatically detect objects of interest in the scene and select the landmarks that would work best for human listeners,” says Clarke.

EurekAlert! PR: http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2015-12/f-ldt120315.php

Study: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01793/full